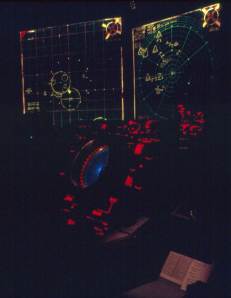

Where I worked was called CIC. This area was manned by those with a rating of Radarman (RD). This rating was changed to OS (Operations Specialist) in October of 1972. We were part of the OI (Operations Intelligence) Division which also included Radiomen, Electronic Technicians, Quartermasters and Signalmen. The job in CIC was multifaceted and included operation of radar (both air and surface), aid in navigation, detect, plot and track friendly as well as hostile targets, communicate with other vessels and basically provide information. Collection, analyzing, processing, display and dissemination of tactical information and intelligence is essentially what we did. There was a reason that we were located just a few steps from the Captains stateroom and had a direct stairway to the bridge. The skipper, the XO or the OOD (Officer of the Deck) could step in CIC anytime and see the big picture of what is going on around us through the use of status boards. These were steel-framed sheets of acrylic or plexiglass that were edge-lit and displayed information. The room was always dark when underway, with nothing but red lights overhead to protect night vision. The status boards stood out brightly in that environment. They would be written on from the back with yellow grease pencils then when viewed from the front, with the edge-lighting, lit up like neon. We had terry rags with which to erase the marks off the panel. Sometimes when at GQ and manning our battle stations I would be assigned to the large status board that displayed the Viet Nam coastline and we would plot various positions of other vessels in the fleet on it. Of course, for the writing or plots to be correctly visible in the room you had to write backwards from the back of this board. You worked from the back of the board so that the information was never obscured from the front. I can still quickly write backwards to this day! Some things just don’t go away. Working with legible logs and sometimes having to jot down codes, I got into a habit of modifying how I print zeros, 1’s, and Z’s to save any confusion. I still sometimes do this to this day, though I’ve never run the slash through a 7.

Where I worked was called CIC. This area was manned by those with a rating of Radarman (RD). This rating was changed to OS (Operations Specialist) in October of 1972. We were part of the OI (Operations Intelligence) Division which also included Radiomen, Electronic Technicians, Quartermasters and Signalmen. The job in CIC was multifaceted and included operation of radar (both air and surface), aid in navigation, detect, plot and track friendly as well as hostile targets, communicate with other vessels and basically provide information. Collection, analyzing, processing, display and dissemination of tactical information and intelligence is essentially what we did. There was a reason that we were located just a few steps from the Captains stateroom and had a direct stairway to the bridge. The skipper, the XO or the OOD (Officer of the Deck) could step in CIC anytime and see the big picture of what is going on around us through the use of status boards. These were steel-framed sheets of acrylic or plexiglass that were edge-lit and displayed information. The room was always dark when underway, with nothing but red lights overhead to protect night vision. The status boards stood out brightly in that environment. They would be written on from the back with yellow grease pencils then when viewed from the front, with the edge-lighting, lit up like neon. We had terry rags with which to erase the marks off the panel. Sometimes when at GQ and manning our battle stations I would be assigned to the large status board that displayed the Viet Nam coastline and we would plot various positions of other vessels in the fleet on it. Of course, for the writing or plots to be correctly visible in the room you had to write backwards from the back of this board. You worked from the back of the board so that the information was never obscured from the front. I can still quickly write backwards to this day! Some things just don’t go away. Working with legible logs and sometimes having to jot down codes, I got into a habit of modifying how I print zeros, 1’s, and Z’s to save any confusion. I still sometimes do this to this day, though I’ve never run the slash through a 7.

On any Navy ship the CIC is often referred to as the nerve center of the ship. For all the information flowing in and out of here, you would think we knew all of what is going on, but it wasn’t always so. We would be in the dark figuratively as well as literally. After having

worked there I cannot imagine being an engineer working down below decks in the engine room or boiler room, totally clueless to what is happening topside. I’m sure that sometimes we weren’t aware of all that was going on since the bridge would often take direct control of a situation, especially if the captain was up there. We had to detect and track radar contacts, then relay that information to the bridge. The surface search radar operater was on the same sound-powered phone circuit as the port and starboard lookouts, so he would alert them to the direction of a contact when it would come within range. We would track a contact and give them sequential sequential NATO phonetic alphabetic names. Unknown contacts or targets were called skunks, thus the first one of the day was Skunk Alpha, then Skunk Bravo, Skunk Charlie, etc. We would have to track them over a short period of time to gather their course and speed. This would have to be calculated taking into account our own forward course and speed. Ahhhh, ya gotta love relative motion! We could then tell the bridge “ Skunk Delta is on a course of 260 degrees at 14 knots and will pass 1000 yards astern of us at 2312.” We would still track it to watch for any deviation and then send updates to the OOD on the bridge.

Within our watch group at any given time there may be one guy manning the surface search radar, another watching the air search radar, someone

listening for radio transmissions, someone keeping a log, someone plotting on the DRT (dead-reckoning tracer) and a floater, probably the Petty Officer of the watch. In between tracking contacts on the surface search radar, the operator would be giving bearings and ranges to geographic features to someone to plot our position on a navigation chart. The bridge had their navigation team too, so we were sort of a backup for that and other reasons why we had to keep aware of our exact location. I remember once an Ensign came down from the bridge with a piece of paper and said here is the latitude and longitude we just got from the aircraft carrier in our task group, “they have a satellite system that tells them exactly where on earth they are.” “Hey, why don’t we have that?” Spendy stuff in 1972 and only the larger vessels had that hardware. Nowadays we have that technology in our wristwatch and cell phones!

Typically, we stood 4 hour watches which would rotate through 3 or 4 watch sections. This would allow you at least an 8 hour period for sleep or other activities. There was usually more shipboard activity during the daytime hours, so CIC was usually more active during this time with different things going on. Contrast that to a mid-watch which ran from midnight until 0400. This one could be quite boring, especially when steaming across the middle of the Pacific. We were no less vigilant, since there was still the chance of encountering commercial merchant traffic, but it was certainly more relaxed. Another reason to stay awake was in case of a man overboard, we would have to immediately mark the position on the DRT and then send ranges and bearing to that location to the bridge for them to get to get the ship back to the area until a visual could be made. In the Tonkin Gulf even the mid-watch could be tense, because anything could happen at any time. If on Yankee Station the carrier we were guarding could decide to launch aircraft anytime, or we could be sent off on a search and rescue. You just never knew.

When in a situation where more personnel was necessary you would go to a 2 section watch system, called port and starboard watches. If you were not  on watch, you were next and you were usually there for 8 hours. When on the gunline or any other time that ordinance was being handled or other imminent threat, the crew had to be at Condition I, or in other words, at General Quarters. An alarm would sound and all speakers throughout the ship would call for “All hands man your battle stations.” You were to react to this immediately no matter what you were doing. If your station was topside you donned a helmet and flak jacket. The smoking lamp is out! You remained at this condition until you left hostile conditions or away from danger. During this condition there were highs and lows of activities with the adrenaline flowing heavy for awhile and then mind-numbing lulls where you could barely stay awake.

on watch, you were next and you were usually there for 8 hours. When on the gunline or any other time that ordinance was being handled or other imminent threat, the crew had to be at Condition I, or in other words, at General Quarters. An alarm would sound and all speakers throughout the ship would call for “All hands man your battle stations.” You were to react to this immediately no matter what you were doing. If your station was topside you donned a helmet and flak jacket. The smoking lamp is out! You remained at this condition until you left hostile conditions or away from danger. During this condition there were highs and lows of activities with the adrenaline flowing heavy for awhile and then mind-numbing lulls where you could barely stay awake.

The next stage of readiness was Condition II. This was like a GQ-lite, where a high state of preparedness was necessary. This allowed crew members to use the head or go get chow and then come relieve the current watch standers to allow them to do the same. I think this is the condition we were in when we conducted harassment and interdiction missions that would go on most of the night. Some of us were allowed to hit our bunks as the gunfire continued through the night. We were just far enough offshore to not be threatened by any shore based fire. H&I missions were where you’re assigned an un-observed area to randomly fire to disrupt enemy movements, positions and suspected transportation routes. Doing so at night creates confusion, disrupts activity and sleep patterns.

Most of the time though was spent in Condition III (wartime cruising) or Condition IV. If I recall, we just stood the regular watches when at Yankee Station on Plane Guard Duty. Plane Guard is when a destroyer or escort follows the aircraft carrier 1500 yards and 5 degrees off the stern of a carrier. You’re ready to respond at a moments notice if a flight crew member gets blown off the carrier deck or a plane goes over or crashes nearby. We’re going to be much more maneuverable than the carrier, plus they may be in the middle of flight ops and cannot deviate from the necessary course and speed. If I recall, all of our plane guard duties during the 1972 WestPac were with the USS Coral Sea (CVA-43). The aircraft this carrier had were A6 Intruders, A7 Corsairs and F4 Phantoms. In May of 1972 we took part in Operation Pocket Money. This was where the Coral Sea launched aircraft carrying mines to drop in Haiphong Harbor. We found out later that the mine drop was timed exactly as President Nixon announced the situation publicly to the nation.

Working in CIC was very interesting, often stressful and other times calm. We worked hard, but we had to have our fun times whenever we could to keep things from getting too heavy. I’ll write about some of those times in another article.

Remember when Archie Bunker (Pat Ellis, sorry Pat) cleaned the coffee pot with scouring powder and got the radar watch and bridge watch sick with the runs?

Great job again Dennis. I can still vision DTG (Days To Go) and PCOD on the status board. Some of the towns on the Vietnam status board were pretty good too. You could do alot with the ones that started with Phuc as I recall. We didn’t know how to pronounce it correctly but had fun with them.

Yeah, like the Dong Dang Cat on a Ha Tinh roof. Remember how hard it was to make the Chief laugh? The large status board had the North Vietnamese coastline and we had locations of things like PIRAZ stations, CAP, Yankee Station, task force locations, etc. I would stand in front of that status board and pretend to be a weatherman giving sweeping motions over the board indicating a “storm front” of MiG-21’s flying in from the Hanoi area over the gulf. Chief Remetch used to crack up at the couple of times I did that.

Lots of interesting names of cities, towns, villages, hamlets, etc. The sickest one though, is the renaming of Saigon after we let the communists have it. Why the hell would anyone live under the name of a cruel murderous dictator like Ho Chi Minh? Would you live in Adolph-Hitlerville?

I was a Radarman on the USS John S. McCain DDG 36 for three and a half years (1969-1973.) Well written piece, and it brings back both good and bad memories, but we made it home alive for some additional “bonus years” of life. Thanks. Well Done Dennis!

Former RD3 Raymond H. Filak (0334)

Thanks for the comments, Ray! You know, we used to say “RADAR spelled backwards is RADAR, so no matter how you look at it, you’re in a world of shit!” LOL

The North Vietnamese coastal waters offshore of Vinh were shallow enough to be good fishing so ships on PIRAZ station were maneuvering through large numbers of fishing boats whenever the weather was good. The bridge made avoiding course changes frequently when daylight observations could be made, but desperately requested CIC assistance during darkness. I recall sometimes the PPI scope looked like someone threw a handful of salt onto it. The little boats wouldn’t paint reliably; and they were often too close together to differentiate on screen. Each boat typically was the living quarters for a three-generation family. We tried to avoid them, but there were often too many to track. One lookout reported a light ahead which turned out to be a guy standing on his boat with a cigarette lighter so we could see him. Another time the bridge was so focused on determining the bearing drift of a boat off the port bow they didn’t notice another boat bouncing down the starboard side of the ship.

What seemed to make the situation worse was a rumored superstition of the Tanka boat-dwelling people of southeast Asia. They reportedly believed evil spirits would follow in the wake of a boat bringing it bad luck until the spirits could be attached to another boat. The way to do that was to have another boat cut close across your wake so the spirits would follow his wake. I can’t substantiate the rumor, but I can remember boats ahead of us seemingly aimlessly wandering right and then left. Just when we were convinced they had sufficient bearing drift to pass safely to one side, lookouts would report them sailing hell-bent across our bow to pass down the other side. On the big cruiser they would sometimes disappear from sight under the bow before emerging unscathed on the other side. The CO finally told the OODs not to confuse the issue with avoiding course changes, but let the small boats use their superior maneuverability to keep out of the way.

Was the situation any different on the gun line off the South Vietnamese coast? Did the junk patrols to intercept arms smuggling reduce the number of fishing boats?

I was on the Francis Hammond’s first cruise in 1972 and went back on the Bronstein (FF-1037) in 1972. I do not remember any IBGB’s on the gunline. On the Bronstein we had 3″ twin gun mounts and had to get within 2,000 yards of the beach to hit any of the targets. It was too hot for any small boats there. I went back again, but not to the gunline, in 1973 aboard the Constellation for the end (the big group hug picture with all of the battle groups).

I was a RM on COMSEVENTHFLT staff onboard the USS Oklahoma City (CLG-5). We were homeported in Yokosuka Japan but spent a lot of time at Yankee Station. One night we were ordered to enter Haiphong Harbor to deliver ordnance against the port. We all knew we would be targeted from three sides and were all pretty nervous about being a single ship entering into such a tight place. I had the midwatch and about an hour in the buzzer at the message window rang and I answered it. Standing there was Admiral Holloway with a handwritten scrap of paper….a message he wanted sent to CINCPACFLT telling him the attack on Haiphong Harbor should be a coordinated attack with multiple ships, not just the “OKie Boat”. I have never in my life typed any faster than that night getting that message to CINCPACFLT. We did sail into Haiphong later, with several other ships. I was in radio and didn’t witness the bombardment myself but we listened to the CIC radios and heard that there were huge secondary explosions on the beach. We were again pretty nervous when CIC talked about torpedo boats attacking. We breathed a sigh of relief when CIC reported the small boats had been taken out!!

Thanks for the memories, chief! I can’t believe anyone would send a single vessel into that harbor, even with the OKC’s firepower. I would think the NVN would have had some heavy gun emplacements on that peninsula on the south side of Haiphong Harbor. Or maybe it’s an island there. I think when you guys went back it was during Operation Freedom Train and the USS Oklahoma City was accompanied by the USS Providence, USS Newport News and some DD’s.

Dennis

I am working on the Battleship Texas restoration of the CIC. We are restoring the ship to 1945 condition.

Do you know if there was a insignia for CIC in 1945?

Ed,

I’m not really sure what you mean. Do you mean an insignia for the CIC itself or for the guys that worked in there like the modern day RD’s and OS’s? Here is an interesting article about CIC in WW2 at http://www.bangust.com/hankcic.htm . Good luck with the restoration.

Dennis

I have alot of C.I.C Combat Information Center magazine’s does anyone know if they are worth anything they are in good condition. 1944-1946?

Justin, I’m not sure of their worth but you can see quite a few issues at http://www.maritime.org/doc/cic/index.htm . You may want to see if anybody is selling them on eBay.

-Dennis

What issues of 1944-1946 CIC magazine do you have?

Contact me at alternatewars.webmaster@gmail.com

I’m interested in purchasing.

Well written story of a proud rate and special select group of men. I spent 20 years as a Coast Guard Radarman aver very proud of the service. BZ Dennis!

RDC Lionel Pinn

USCG Retired

I love this. Thank you. If you’re still monitoring this page, I’m curious what additional duties a CIC onboard a carrier has and if any of these responsibilities moved to ATC aboard the carrier.

Matt,

I can’t really tell you other than I think it would be quite similar. By ATC I’m guessing you mean Air Traffic Control. ATC could be a part of CIC or it could be its own area, I just don’t know. On the USS Francis Hammond we had only one person in CIC qualified for ATC and that was RDC Remetch. Carriers certainly must have more! One time I provided a vector to a helo to get back to DaNang through some weather, since nobody else was around. I probably could have got my hand slapped for that, hehe.

I did spend 10 days aboard a carrier when they needed temporary crew for some war-games off of Baja in 1970 or ’71. On the USS Ticonderoga it seems like we were always at a modified GQ status with port and starboard watches. I don’t really recall that much about their CIC other than it was way older than on my boat, a brand-spanking-new Knox class DE.

Dennis

Dennis: I found your blog searching for “Skunk Delta”. I posted a link to it in a thread about the two recent ship collisions on freerepublic.com.

http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/news/3581874/posts?page=1

This brought back many memories of my time in CIC on the USS Forrestal 1967 to 1969. I was a watch supervisor in the Air Search CIC after I made RD3 and spent my first 6 months on the ship as a lookout on the open bridge. When at sea we worked 6 on 6 off. Our Surface Search area was on the bridge in a compartment right behind where the Captain sat. I also was on board when the disastorous fire happened in 1967.

Nice write-up. Brought back a lot of memories. Served on-board Downes (DE 1070) from commissioning (1971) until 1974. Reported as a RDSN and departed as OS2. Instantly recognized the pictures of the stat boards and the radar and IFF consoles. – even after 45 years!